A few weeks ago I had my day in court. I witnessed “Operation Streamline”, the court system that speeds up “due process” for the thousands of immigrants who have entered the United States illegally. Operation Streamline first began back in 2005, and was instituted during George W. Bush’s Presidency. Any American can sit in the courtroom in Tucson and observe what happens to approximately 70 undocumented migrants every day, Monday through Friday. It is an eye-opener.

It all happens in the Evo A. Deconcini U.S. Federal Courthouse in Tucson, Arizona. Just getting into the Courthouse is a sobering experience. Think airline security measures, and multiply by 10. I had a camera and iPhone in my purse and was not allowed past the security checkpoint in the lobby. I knew no photos were allowed but thought I could carry a camera or iPhone into the building. Wrong. Running across the front courtyard of the Federal Building I found a cafe that held my camera and cell phone for several hours while I hurried back just in time for court proceedings to begin.

Long may she wave

The courtroom is large. The benches look like church pews. As I enter the space, I notice that the left side of the room is filled with brown faces all seated on the hard benches, and on the right side are small groups of predominately white men in uniform milling about. Fifty-seven migrants sit quietly and stoically on those benches. All are Latino. They are dressed in t-shirts and dusty jeans and look like they have been in the desert for days. Their belts and shoelaces have been removed. There are two female migrants who sit separately from the men. All are in shackles—their hands attached to a chain around their waist, with feet manacled at the ankles. I watch as a migrant tries to drink water from a paper cup. It is impossible to drink without bending over at the waist and precariously ingesting the water against gravity. The water spills down the young man’s t-shirt as he tries to take a sip. When they stand, some of them have difficulty keeping their pants up without a belt. I am embarrassed to watch this and quickly look away.

All eyes are on our little group of six as we enter the courtroom and are told where to sit, which is on the far right side of the room. The looks from the migrants are beseeching, searching, as if we might be family or a friend? There are a few smiles from the migrants. I smile back, tentatively, not quite knowing how to behave in this setting where justice presides.

One fellow has on baggy “skater” shorts and a silky soccer t-shirt. He looks like a California dude, and is heavier and larger than any other migrant. He grins at our group and gives us a little wave.

The men in uniform on the right side of the room are Border Patrol officers and U.S. Marshals. The atmosphere is one of laughing, joking, a feeling of business as usual and easy camaraderie. Several are playing with their Blackberries.

view from the courthouse

On the left there is silence as the migrant defendants stare into their lap or vacantly straight ahead. I notice that one of the lawyers and a Border Patrol officer are also Latino, and it occurs to me that they are the only Hispanics in the room that are not in shackles. The majority of migrants look young—in their teens, 20’s or early 30’s. All have earphones which are translation devices so they can understand the court proceedings which are in English. They each have a federal public defender who has spent the morning with their assigned cases—usually about six migrants per lawyer. An attorney friend who works a day each week doing Operation Streamline cases has told me that these are perhaps “the nicest people that I defend. Their only crime is crossing the border to find work.” My friend is supportive of the migrant’s plight, and gives me insight into the proceedings of this streamlined form of justice. He doesn’t approve of the cookie-cutter approach to Streamline, but is as supportive and informative to the migrants as he can be. It is a tough job. I have to say that I am impressed with all of the attorneys that day. They take their job seriously and do their best to be fair and just and supportive of their clients.

Walking the Wall to the comedor

When the judge enters, we all stand. The judge is a woman, the Honorable Jacqueline Marshall. As she takes roll call with each migrant, she pronounces every name correctly in Spanish. She is patient and empathetic with each person. I am impressed with her demeanor and her caring, coupled with her objectivity as a judge.

One fellow does not know his birth date, and she speaks with him about his best guess regarding his age. He decides he is “maybe nineteen.” Another fellow states his birthplace as Guatemala, when it is actually in Chiapas, Mexico. It turns out that Chiapas was part of Guatemala 180 years ago, and was annexed by Mexico. This man’s family has never accepted the change. This business of borders exists far beyond our own.

The migrants are called to the bench in groups of six. Their bony frames are hunched over from the weight of the leg irons and manacles. The clanging of the metal irons and the shuffling to the front of the room is a sight I will never forget. I think about drawings of African slaves in this country two hundred years ago.

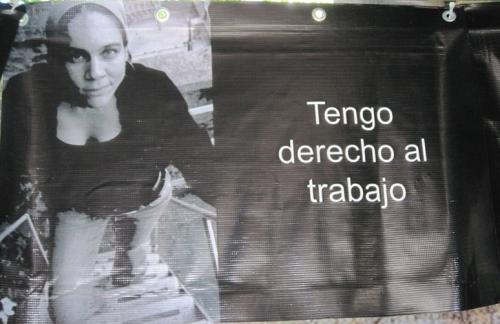

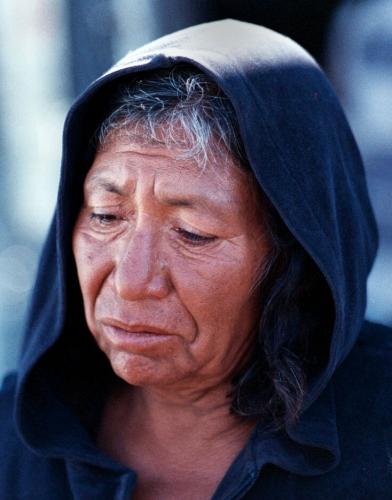

Considering the next step at the comedor

Each migrant is asked:

“Are you a citizen of Mexico (or Guatemala, El Salvador, Honduras) and did you enter into the U.S. illegally?”

“Si”

“Are you being forced to plead guilty?”

“No”

“Have you spent time discussing your situation with your lawyer?”

“Si”

After several more questions, the judge asks:

“How do you plea?”

“Culpable,” or “guilty,” rings out in the room, one by one.

The California skater dude says, “Guilty”, and tells the judge that he was visiting extended family in Mexico and was trying to get back home to Tucson when he was detained in Nogales. He speaks perfect English. He looks like a high school kid.

Each migrant is given the opportunity to speak. The day I was in court, no one did. All know that by pleading guilty, they will get back to Mexico quicker. They have been advised by their lawyers well. The migrants have the right to a trial by jury if they wish to plead “not guilty”, but this means weeks in a prison or detention center awaiting trial, and the probability that they will be deported anyway. Not much of a choice.

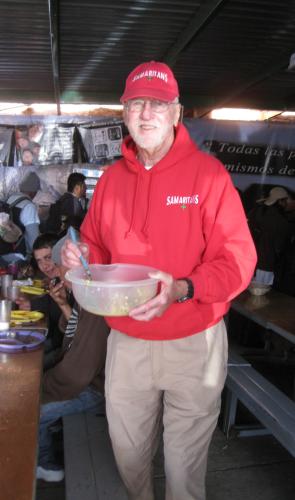

Arriving at the comedor

If this is a first time offender, the sentence is 15-30 days, with time served counted as part of the sentence. If the migrant has other charges (a theft, driving without a license, for example), the sentence is longer (30-180 days), but by pleading guilty, the lesser offense is what is considered when a judgment is made. Sometimes the sentencing seems arbitrary, but it appears that the judge has more information about each migrant than is evident to all of us in the gallery.

So, the question that occurs to me is, does this work? Does this conveyor belt approach to justice deter illegal entry into the United States?

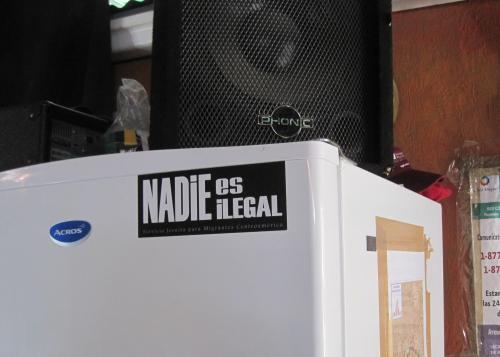

The newspapers and media tell me that the numbers of migrants are down. The Border Patrol apprehend 1000 migrants/day along the Arizona border, and seem to cherry-pick seventy of them for Streamline. The rest are quickly deported into Nogales, now the busiest exit point in the state. The comedor in Nogales, Sonora, is seeing record numbers these past months—two hundred or more per day.

In the past six months (October, 2011-March, 2012), there have been 71 dead bodies found in the Sonoran desert. That is more than ten per month. Most of the migrants I see in Nogales, Sonora, tell me that the only things that deter them from crossing are poor economic conditions in the U.S. and the harsh dangers of the desert journey. And even these deterrents do not dissuade many from seeking to reunite with families and loved ones. They will cross regardless of Streamline or incarceration.

And here’s something to ponder. The numbers of Border Patrol apprehensions began to decline in the year 2000, five years before Operation Streamline. When I look at graphs with numbers of immigrants, they seem to reflect the ups and downs of our economy. So what is Operation Streamline really accomplishing?

And what about the cost? As I sit in the air-conditioned chambers of the U.S. Federal Courthouse in Tucson, sitting on these hard Presbyterian type benches watching judgments come down from on high (and the judge is up on a platform), I wonder about the dollars spent on Operation Streamline. It is hard to pin down an accurate monetary figure. As usual, there is no easy answer. First there is Homeland Security (which includes the Border Patrol and ICE). Their budget in 2010 was 3.6 billion dollars. Obama increased this budget by 600 million in a special supplemental package for even more border security. Then there is the Wall at the U.S./Mexico border, which is presently a 42 billion dollar project, and growing. Add to this the incarceration facilities and the growing private prison system which is headed up by the Corrections Corporation of America. The privitization of the prison system is a controversial topic in itself. A monthly check of 13 million dollars is paid to this corporation by the U.S. Marshal in Arizona. The private prison system is Arizona’s growth industry. We’re talking a major job stimulus program here, folks. If you have a penchant for emotional detachment, disengagement from people, and like to wield some power, well, there are jobs for you with Corrections Corporation of America.

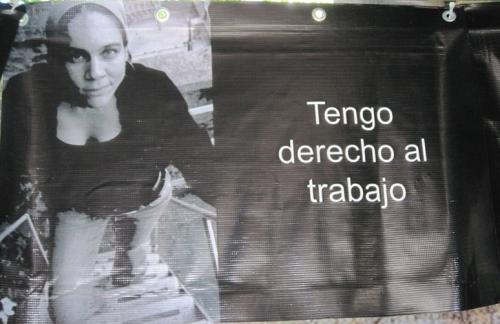

"I have the right to work"

If this is all a bit complicated and confusing, you are correct. I read recently that a number of migrants are picked up by the Border Patrol heading south, back to Mexico. What??!! Why would this be happening? One explanation is that the Border Patrol must beef up their numbers in order to keep this financial boondoggle going. You know the drill—spend the money or it won’t be in the budget next year. If their numbers drop, there is less money, less jobs. So if a vehicle is heading back to Mexico and is 5 miles from the border, it is easy pickings. Detain the vehicle and process the migrants through the system. The courts, the prisons, the law enforcement agencies all prosper.

And the taxpayers foot the bill.

Forgive me for getting carried away with this travesty. To me the biggest cost is the humanitarian one–criminalizing people who have not committed a crime. Watching fifty-seven people in chains and manacles shuffling through the courtroom with the American flag in full display is unnerving. Watching this spectacle knowing that their crime is crossing the U.S. Border looking for work touches me at a visceral level. This is what my own ancestors did when they crossed the pond just three or four generations ago. We are criminalizing people who want to work.

Most of the people I witness in that courtroom are going to make it, either here or back in their country of origin. This is their odyssey, not unlike Homer’s tale of The Odyssey. There are monsters to slay, sirens that will offer temptations, cyclops to tackle, and a journey of danger and daring. The myth of The Odyssey has come to life a few miles from my home. The migrants in this courtroom may leave the room shuffling in chains with their head down, but they will not give up. Neither did Odysseus.

As I watch one of the migrants leave the courtroom in chains, he tries to cross himself. His chains restrict his movement. Watching this simple, eloquent gesture stays with me the rest of the day.

So here’s what I take away from this profound day in court. If there is a chance for a better life, be it here or somewhere else, these people in chains are going to take it. And probably succeed.

I really believe that.

Research for this posting is from the following:

Tucson Citizen, Oct. 21, 2010, “Operation Streamline, SB1070, CCA, immigration and private prisons, and how it all connects”

Operation Streamline Watch, grassrootsleadership.org/operationstreamline, Sept. 7, 2011

Operation Streamline Fact Sheet, July 21, 2009

Sonoran Chronicle: sonoranchronicle.com/tag/operation-streamline/

If you wish to read more about this topic, Google “Operation Streamline Tucson.” A list of references will come up for your perusal.

Be sure and check out the Green Valley Samaritan website at: www.gvsamaritans.org Many readers have asked how they can support the Samaritans. The website is the place to learn of our activities, mission, and how you can support the work.

Posted in Uncategorized

Recent Comments