It’s Tuesday morning, my day with the Samaritans at el comedor. I look out the window and there are a couple of inches of snow on the ground. Big fluffy flakes are falling, and the desert is transformed into a surreal fairyland of silver and icy blue in the early morning hours. The day is fraught with the usual mayhem, as I rush around looking for my passport, scraping snow off the windshield, and rummaging through drawers searching for gloves and a warm hat. It is so quiet outside. Even the birds are silent with their feathers all puffed out to twice the size. They look like fluffy marshmallows sitting in the branches of the palo verde tree. Facing east on this crystal morning, they wait for the sun.

Driving out the gate of our ranch I spy two coyotes just meandering through the desert mesquite. They appear healthy and fat, their furry coats thick with a reddish cast. These wild creatures stop, give me eye contact, and just stand there twenty feet away. I roll down the window and we spend a moment gazing at one another until they silently stroll off into an arroyo and disappear.

I think about what draws me to living in the Sonoran desert. There is a mystical feeling to life here. Today I am seeing the world as if in a dream. The mundane and commonplace seem awesome and inexplicable. There is no logical or psychological explanation for this awareness, but my connection to the coyotes and to the beauty of the snow-covered desert this morning feels as tangible as the frozen ground beneath my feet. Reality has taken on a supernatural keenness. There is an element of surprise in the air.

Walking to the comedor today with my Samaritan colleagues is a cautious, circuitous trek through ice and mud. Construction workers are bundled up continuing their work on the expanded port of entry and the ongoing building of the wall. The digging and building and disruption is endless. Carefully making our way through the maze of temporary pedestrian paths, we hang on to each other and the barricades that are sporadically placed along the way.

When we reach the comedor, there are space heaters cranking out as much heat as they can muster, and a group of migrants are huddling inside the shelter looking cold, wet, and hungry. Many have blankets draped around them. Sister Lorena plays a short video film projected on the wall–a snow scene with Bambi and some deer frolicking in the snow. Everyone laughs at the incongruous scene of snow and deer, and it feels good to be in this room of people making the best of an uncomfortable situation. The mood is upbeat as we pass out the plates of beans, eggs, and a chicken pasta dish.

Then Sister Lorena turns on the CD player and “Ode to Joy,” the last movement of Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony, fills the room. To my surprise, most of the migrants hum along with the melody. The whole room seems elevated as we work alongside the migrants cleaning up the breakfast dishes. The comforting smell of coffee permeates the damp cold. The migrants leave the shelter wearing the gloves, socks and jackets that we have brought this week. The sun is beginning to peek through the grey of this frigid morning. There is magic in the air. My ordinary life today seems extraordinary.

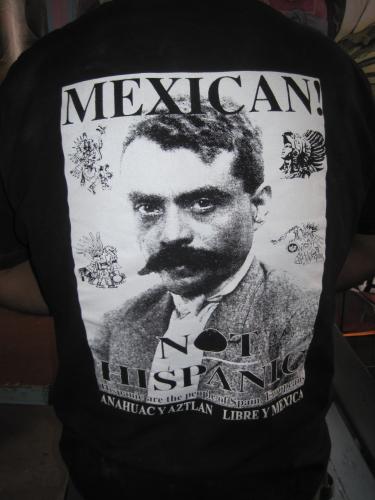

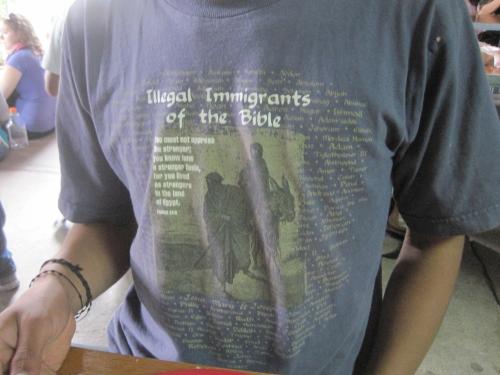

I think about a man I met a few weeks ago. His story was one that transcended the normal boundaries of reality. I first noticed his t-shirt which boldly stated “Mexican! Not Hispanic.” In tiny letters the t-shirt read: “Hispanics are the people of Spain—European.” My migrant friend was eager to discuss the politics of Spain and Mexico and how he views these differences. He was affable and wanted to talk about his near death crisis in the desert.

His name was Alan, and he told me he was “pure Mexican” from Veracruz. I asked him how he came to be at the comedor, and his story exceeded the boundaries of my normal, everyday world. He took my Samaritan colleague, Ricardo, and me aside to a quiet corner and with great emotion began to tell us about his experience while lost in the desert. He was abandoned by his coyote guide after four days because he could not keep up with the group. One member of the party had died a few days before, and he tremulously spoke of passing by the body laying on the ground. The weather was freezing at night, and Alan had run out of water and food. Things were not looking good as he stumbled alone through the desert looking for help.

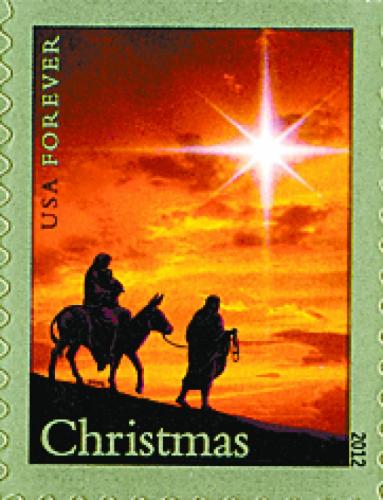

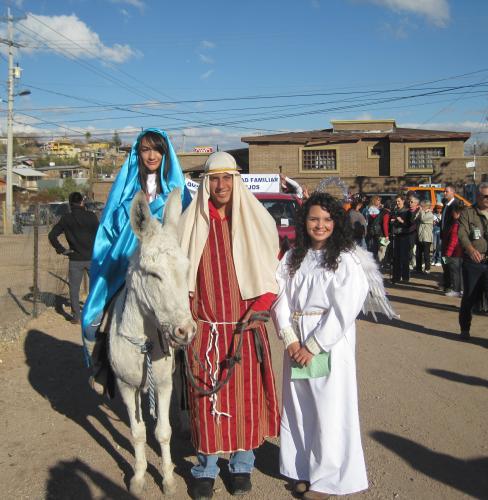

Alan was no longer able to walk and fell to the ground. He woke up in the early morning and saw the migrant who had died “running in shorts and a t-shirt” beside him along the migrant trail. There was a dusting of snow on the ground. He saw the dead migrant’s footprints. The spirit migrant told Alan to “go home to your family.” Alan did not heed these words, and continued on. Soon “an angel appeared to me and told me to turn back and return to my home in Veracruz where my family awaits.” When he looked ahead, he saw a road and “la migra,” the Border Patrol. The angel stood beside him and the Border Patrol did not see him. He was invisible to the agents and was protected by this guardian angel. Alan ignored the angel’s commands to return home, and continued on the migrant trail alone.

After several hours he spotted the coyote guide that had abandoned him, standing beside a waiting van. The angel appeared at this moment with his arms folded, disappointed that Alan was not paying attention to his directives. The angel told him, “Your service is now to God and your family. Go home!” Again, Alan ignored the angel’s command and joined the coyote and migrant group, getting in the van. Alan tells me this with certainty and punctuates each word with his fist. I got the feeling that Alan knew this was a wild tale and difficult for us to believe, but he was absolutely grounded in the reality of his experience. He described his ordeal in detail. This was his truth, and the truth penetrates to the heart.

Eventually, Alan, the coyote guide and the migrant group were picked up by the Border Patrol and taken to a detention center. He was deported to Nogales and sought shelter and counsel at the comedor.

Posing as the angel, he balanced on one foot to show me how the angel stood on a rock. Then he physically assumed the posture of the running spirit migrant who died. It was a magic tableau which came to life over in the corner of the hectic, busy shelter. The drama of the event was reenacted for Ricardo and me, as Alan showed us how he touched the wings of the celestial being out in the middle of the desert just a few days before. Alan was trying his best to put into words the spiritual essence of his experience.

We helped Alan purchase a bus ticket back to Veracruz. He finally acknowledged that the angel was right. He must go home to his family. Our migrant friend was tearful and emotional when we wished him a safe journey. I took a photo of him in his political t-shirt.

So I looked at Ricardo, and asked, “What do you think happened out there?”

Ricardo, an avowed non-believer in such things as angels and spirits, answered, “Well, he was probably hallucinating from no food or water and the freezing temperatures. I think he almost died. But something must have happened that helped this man survive certain death.” We were both quietly shaken with Alan’s story.

I surveyed the room taking in the 100 or more migrants shivering in the morning air, and thought about all of the stories of survival and miracles that every one of them could tell us. There are 100 books in this room waiting to be written.

I am witness to tragedy and miracles each time I come to the comedor. There are so many stories, I don’t know what to do with them all. I will remember Alan’s energy and vitality when telling me his tale of survival. His is a world that promises not only joy, but a fair share of misery as well. He has taught me to look at the world with new eyes. It is the world of Mexico and the borderlands. It is magical realism.

And I love being privy to the magic of it all.

Find out more about the Green Valley Samaritans on their website: www.gvsamaritans.org

The Kino Border Initiative is the binational organization which directs the humanitarian activities at the comedor. Their website is: www.kinoborderinitiative.org

The Santa Cruz Community Foundation supports the cultural, humanitarian and economic programs of the U.S./Mexico borderlands. Bob Phillips, the director, can be reached at: (520) 761-4531

I endorse the activities of these organizations. They are all angels. Peg can be reached at: Pegbowden@yahoo.com

Recent Comments