How we say things makes a difference.

In my conversations about the issues that matter to me, I tend to gravitate toward people who share my views. I massage their egos and mindset, and they massage mine. We smile, nod our heads in agreement, and offer variations on the same theme.

Seven months ago I received a call from Montreal, Canada. A TV series focusing on contentious borders throughout the world was being developed, and the Arizona/Mexico borderlands was of interest to the Canadians. The premise was intriguing and creative: Interview people who hold strong views about Latino immigration on all sides of the spectrum—those favoring comprehensive immigration reform, and those preferring closed borders and increased deportations. Then sit them down to a gourmet dinner prepared by a French-Canadian chef, and have a dialogue about these issues. The series will be called: “Dining With the Enemy.” The Canadian crew wanted to learn about Arizona and its evolving relationship with Mexico.

The Canadians planned to film borders in Gaza, Colombia, Chiapas, Rwanda, Afghanistan, Korea and Pakistan. They were young, adventurous, focused, and professional. And, I might add, they were fearless. We met at a local cantina the day after their arrival, and we mutually checked each other out. They spoke French, English, and a smattering of Spanish, often in the same sentence. I couldn’t understand half of what they said. I liked them immediately, as they were open to the varied politics and viewpoints of the people of the borderlands. They were fiercely passionate about their French-Canadian roots in Montreal.

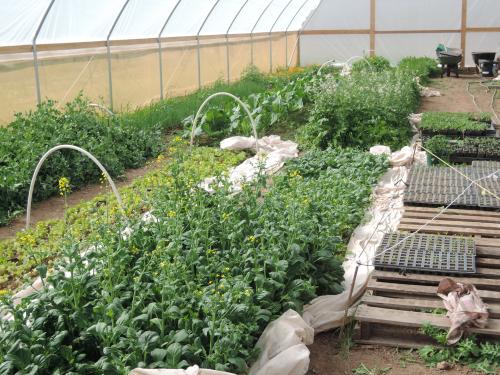

Plus, they were interested in regional cuisine. I am a foodie, a person who enjoys and cares about food. Listening to the culinary dreams and plans of Charles, the chef, I was immediately hooked into the idea of sitting down to a delicious meal and having a civilized conversation. Charles rhapsodized about the organic farm where our dinner would take place at the end of the week. The organic meat, the lush greens and vegetables, cooking and presenting good food as a way of breaking down political barriers–it was an intriguing idea.

I told them that I was in. I couldn’t wait for the dinner.

Martin, the director and shepherd who herded this motley crew, did his best to keep everyone together. Their van was full of cameras, lenses and various batteries and microphones. The travails of getting them back and forth through Homeland Security would take up another blog posting. There were issues, but we all persevered.

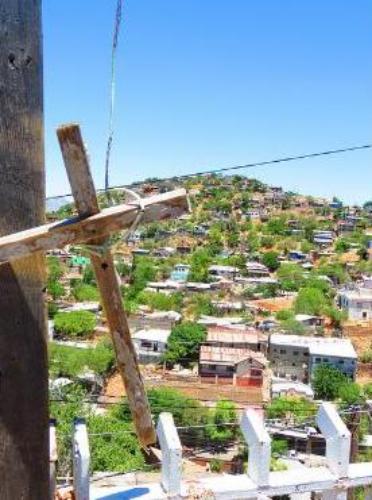

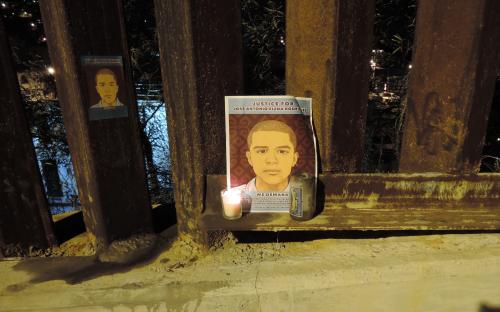

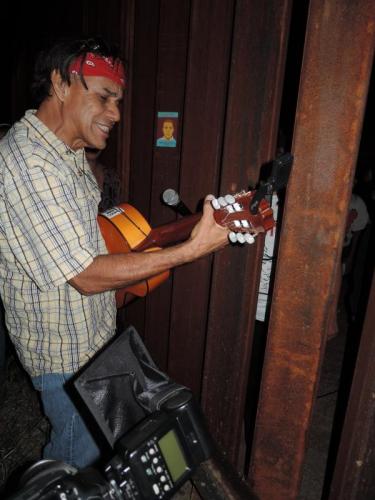

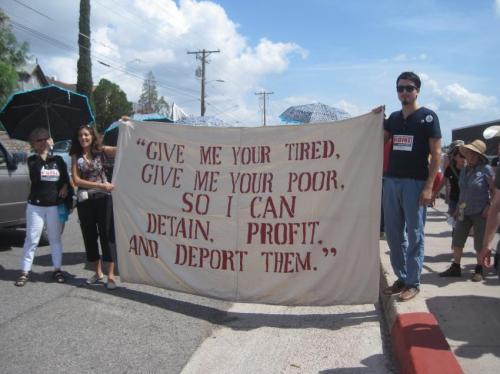

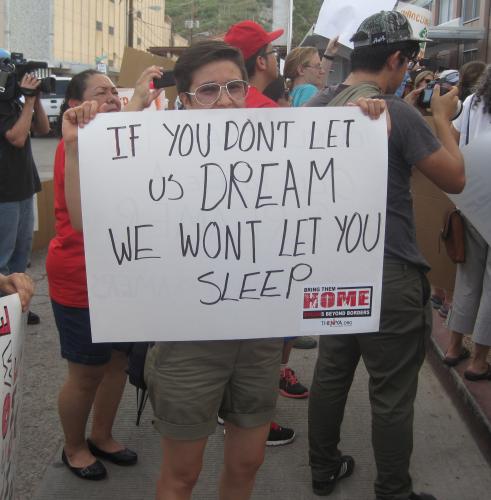

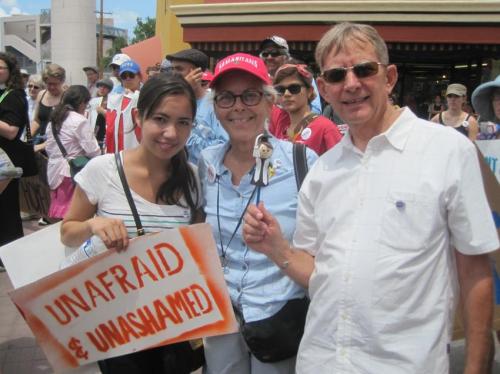

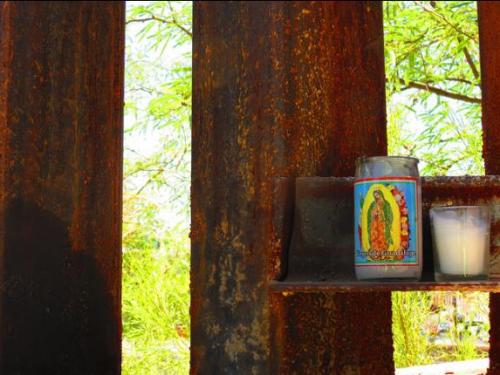

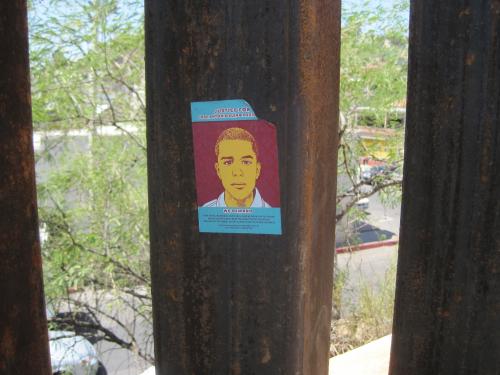

We met for several days doing walkabouts in Nogales, Sonora, and setting up interviews with key people. Included was the mother of José Antonio Elena Rodriguez, the 16 year old Mexican boy who was shot in the back seven times by a Border Patrol agent in 2012. The case has never been resolved. The crew attended the monthly vigil at the killing site on March 10, and interviewed many of the participants. They also set up interviews with a minuteman vigilante, a retired Border Patrol agent, a local farmer who sees a lot of migrant traffic through his property, and a DREAMer who is from North Carolina and has applied for DACA, the Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals. We spent a morning at the comedor where the crew filmed migrants and aid workers, and also walked to the cemetery where many of the migrants sleep. Hours of film were shot over five days.

On the last night of the TV shoot, Charles, the French chef, hovered over the grill at the Walking J Farm located near Amado, Arizona. He was grilling herb encrusted pork chops that were an inch thick, procured from the black hogs I saw grazing in a nearby grassy field. I could smell the sizzling meat one hundred yards away. Roasted baby turnips and carrots, a “flower salad” made of flowering broccoli plants, and oven-cooked kale with hard-boiled eggs completed the elegant dinner. Dessert was a special cake with whipped cream from the farm’s dairy cows. The dinner was topped off with a very good wine, a chardonnay from the Pacific Northwest.

Before dinner, we walked around the farm and looked at the spring lettuces, smelled the thousands of green onions poking through the loamy soil, and admired the resident peacock strutting his stuff with plumage on full display. The weather was a perfect 75 degrees with a slight breeze; the sunset was spectacular. All of the food was grown on the Walking J Farm, a diverse, self-sustaining farm that feeds local families and communities in the area.

The guests included a retired Border Patrol agent, the owner of the Walking J Farm, a DREAMer, and myself. The minuteman vigilante refused to participate in the dinner and was not present at the table. I confess I was secretly relieved at this news. In fact, stepping into this dinner, I felt like I was stepping into Afghanistan. It was a minefield of the unexpected.

Frédérick, the moderator of the series, sat at one end of the table, and Charles sat at the opposite end. None of the invited guests had ever met before the dinner, and so there was a fair amount of nerves and anxiety prior to this savory experiment in diplomacy and dialogue. We chatted it up prior to the supper, and I discovered that one of the guests, Dave, is an active leader in the Tea Party. Cinthia, the DREAMer, entered the US nine years ago through a tunnel with her family. She lives in North Carolina. Jim, the Walking J Farm owner, frequently encounters migrants crossing through his land.

By the time we sat down on hay bales at the log table under some shady trees, we were hungry and already engaged in an animated conversation about living in the borderlands. Here are some of my reflections on my dinner with the enemy.

It was intense. We all definitely had our agendas. Listening to opposing views without interruptions is very difficult. We were all debating, giving voice to our own ideas. Some members talked more than others. Frédérick, our moderator, did his best to rein in the verbosity, asking some good questions.

“What about comprehensive immigration reform? Can you agree that the US needs this?”

“What about decriminalizing illegal drugs?”

“If you had the power, would you deport Cinthia, who is sitting at this table?”

“Would you be willing to pay more for foods and other products from Mexico and equalize the economic disparity between the two countries?”

We tried to find some common ground that we could agree on.

Alas, we could not unanimously reach an agreement on any of these questions. I was discouraged and frustrated with my dinner mates. I very much wanted to have a dialogue that would reduce stereotypes and increase mutual understanding. But the longer the dinner continued, the more entrenched and intense the conversation became.

And yet I learned something. Even though I had spent several hours with three strangers, with some of whom I was intractably opposed, I changed the way I viewed them and related to them. We each maintained our commitments that underlie our views. We didn’t waver much. But we respected each other as the dinner came to a close. I saw the goodness in each of my dinner mates. Maybe that is a first step.

I was hoping that we might come up with some collaborative actions that would really lead to some sort of breakthrough.

That didn’t happen.

We did discover a few shared values: All human beings need to be treated with respect and dignity; there are too many deaths in the desert; we need to dialogue (not argue) with people who do not agree with us.

So I ended up liking my dinner mates, and would probably sit down with them again. Dave, the Tea Party activist/retired Border Patrol agent, gave me a hug at the end of the evening. Jim, the organic farmer, told me he keeps a stash of granola bars and bottled water for passing migrants. I plan to buy some of the Walking J’s farm produce at local outdoor markets in the area. Cinthia and I will probably cross paths at future events for DREAM activists.

I learned that life in a democracy suffers when we only listen to people who share our views. We become selectively informed, and thus, selectively ignorant, becoming increasingly blind to our own ignorance. We need to listen to opposing ideas and try to find a place of connection. We need to quit trashing the other side and stop competing. We need to dialogue rather than debate.

We need to shut up and listen. All of us. We need to try harder.

“Dining With the Enemy” will be aired sometime this autumn. I will post the link when the series is released in Canada.

**********************************************************************************************************************************

I want to thank the Canadians, Martin, Charles, Frederick, Van, and also Oscar, a Tucsonan, for a marvelous week of adventure and conversation.

The Walking J Farm is an oasis of organic abundance, located in Amado, Arizona. Their website is: www.walkingjfarm.com

Please direct your comments and thoughts to Peg Bowden in the “Comments” section of the blog. I can also be reached at pegbowden1942@gmail.com

If you wish to receive regular postings (usually once/month) to this blog, register in the Announcement List space in the right-hand column, and you are automatically on the email blog list.

The Green Valley/Sahuarita Samaritans is a non-profit organization whose mission is to prevent deaths in the desert. Information and contributions can be directed to: www.gvsamaritans.org

Kino Border Initiative directs the activities of the comedor in Nogales, Mexico. The mission is to help create a just, humane immigration policy between the United States and Mexico. Their website is: www.kinoborderinitiative.org

The Border Community Alliance is an exciting new organization in southern Arizona focusing on the economic, cultural and humanitarian needs of the Arizona borderlands. Non-profit status is pending. Their website is: www.bordercommunityalliance.com

Recent Comments