There are three of them, two men and a young woman, and they speak nary a word. There is the usual mayhem this morning at the comedor with the chatter of Spanish and English intermingled. These three look lost, forlorn, and frightened as they watch the others going through the piles of clothing and blankets.

I approach one of them, an older gentleman, and ask him, “Where is your home?” It is one phrase I know in Spanish: “Donde esta su casa?” He looks at me and shakes his head. His eyes are a thousand miles away. He is with a young boy, perhaps 14 years old, who says nothing and gives me no eye contact. There is a young woman who is crying and rocking back and forth on a bench. She is part of this traveling trio. She tells me in Spanish that they are from a village six hours from the city of Oaxaca and they desperately want to go home. The main dialect of this village is not Spanish but a language that no one here at the comedor speaks. Thankfully the young woman speaks Spanish and we are able to piece together part of their story.

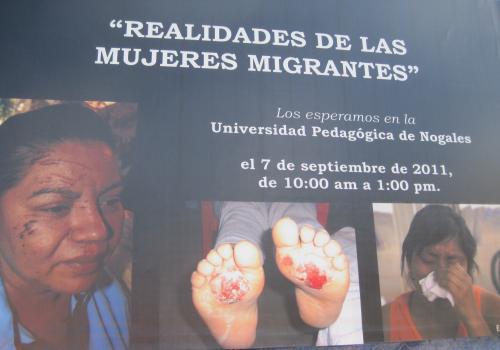

I have been coming to this shelter on the border of Arizona and Mexico for almost a year now, and this is the most traumatized group of immigrants I have seen. The woman is limping, and shows me her knee, which is twice the normal size. I want to apply ice, wrap the knee in an Ace bandage, offer the woman some Advil. Unfortunately the small clinica that was conveniently located across the street from this shelter is now closed. The rent was raised, and the Jesuits who operate the comedor can no longer pay the monthly fee. The relocated clinic is at least three blocks up the street, and there is no way this woman can walk this distance today.

The two men accompanying her are dressed in tattered jackets and carry blankets under their arms. The temperature these nights has been below freezing. The young woman tells me that they have been four days in the desert and were picked up by the Border Patrol and deported to the Nogales immigration authorities. The older man is her uncle, the younger boy her nephew.

Trying to hold herself together emotionally, the young woman tells me she has a baby who is two years old and very sick. The baby is with the grandmother in the village outside of Oaxaca. There are many tears as she tells me of her baby, the illness, the journey, why she was trying to cross the U.S. border. I understand maybe half of what she is saying.

So like good Samaritans, we all march over to the bus station to try and help this little group of refugees. Sometimes the Mexican immigration authorities will pay for a bus ticket home if there is a baby involved. Well, there is a baby involved, but the baby is more than thirty hours away by bus in a tiny village in the jungles of the state of Oaxaca.

Bus tickets for the three of them will cost $298. Plus they need money for food for the long bus ride. We empty our pockets and come up with $100 and change. Once again the manager of the bus station lets us pay for one ticket, and we write an IOU for the balance to be paid in one week. I am sure angels reside in this bus station. There are high fives all around. Even the older gentleman cracks a smile as these crazy Americans dance around the office of the bus station.

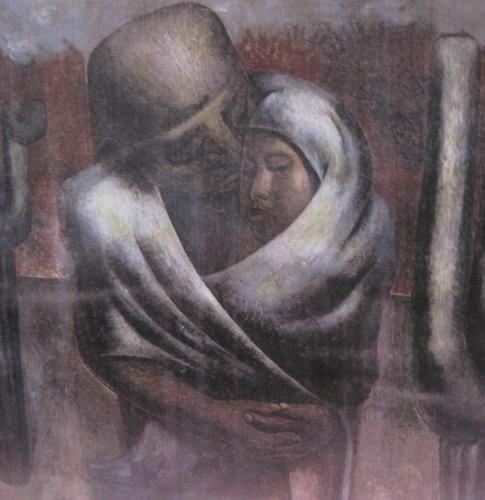

And the young woman teaches us to say “safe journey” in her native language. It is a sweet moment. She asks us to repeat the phrase after her, and we struggle with the strangeness of the new words and syllables. But we do it. And she approaches each of us and offers a hug. She is crying, and to be honest, we were all tearful at this point.

I think about this little group of migrants later that night, and worry about how they will get home after they arrive in the city of Oaxaca, their destination by bus. They still have another six hours to go. But there is a steadfastness and grit here that always amazes me.

No matter how beaten down, my migrant compadres pick themselves up and move on. It is an indomitable spirit that keeps me coming back week after week.

Recent Comments